From the inability to travel around the world to people going into unemployment, COVID-19 has presented a lot of problems to many of us. However, a group of people have suffered a lot more and yet remain invisible in the eyes of the government — stateless people.

A stateless person is someone who has no nationality and is not tied to a country. According to the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are at least 10,000 stateless people in West Malaysia alone with unknown numbers in East Malaysia. Stateless people are denied basic rights like education, jobs, and even healthcare as they do not have any form of identification. So when a global emergency happens, like the COVID-19 pandemic, what happens to the stateless person?

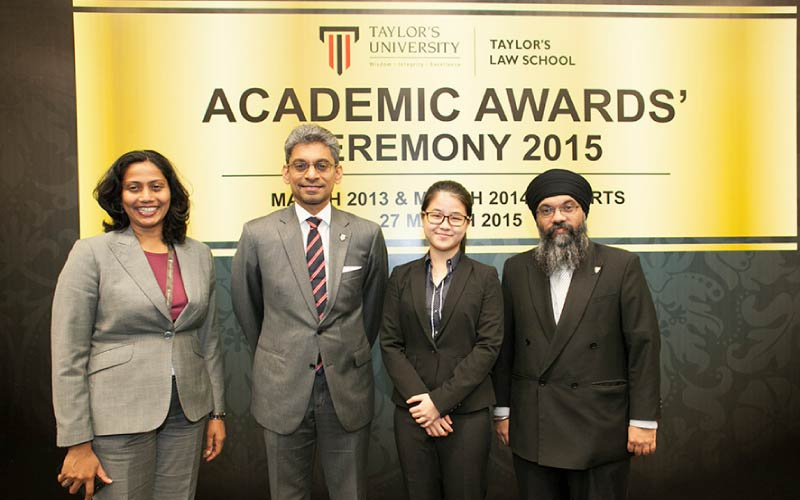

Completing her Bachelors, Masters, and later PhD in Law, Dr Tamara Joan Duraisingam, Senior Lecturer from the Taylor's School of Law and Governance (Fomerly known as Taylor’s Law School), has dedicated most of her career researching statelessness, refugees, and migration in Malaysia. She shares with us her journey of going into this field of research and her expert opinion on how we can help our stateless brothers and sisters.