The Origins of Human Genetics

Our evolutionary tale truly began when the Homo erectus, the oldest known early humans possessing modern human-like body proportions and originating in Africa approximately 1.78 million years ago, migrated out of Africa to Eurasia, forming the Zhoukoudian Peking man of northern China and the Java man in Indonesia, before returning to Africa as a completely new species — the Homo sapiens, the scientific term for us modern humans. Research shows that we evolved to have comparatively larger brain sizes than the Homo erectus, among other features.

But what caused these changes?

In an excerpt of his diary, Charles Darwin wrote, “...existing animals have a close relation in form with extinct species”. Putting it simply, he conceptualised the birth of a new species as an after-effect of environmental pressures, such as climate, food sources, and environmental threats, thus forming the basis of evolution. Essentially equating evolution with the natural process of ensuring a particular species survives as time progresses.

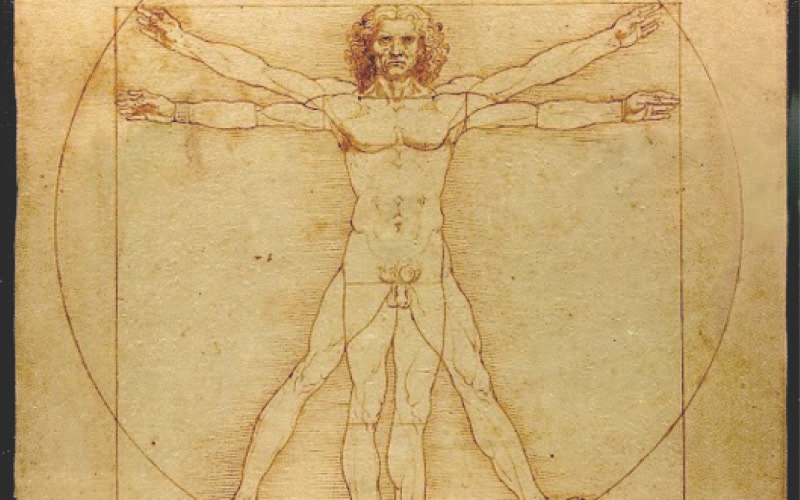

He was well aware that a diversity in physical features enabled the survival of a species through these selective pressures. What he missed was that the underlying basis of this physical variation arose from the microscopic workings of the genome; a long string of genetic codes that give every life on earth variations in their forms and function.

Like with any other animal, sexual reproduction, migrations, and genetic mutations create genetic diversity, enabling ancestral species to adapt to the selection pressures that’d have otherwise wiped them out if they were similar in genetic makeup. Even in the Himalayas, you’d see, spanning across the Tibetan Plateau and the Indian subcontinent, the genetic diversity is moulded within the Nepalese subgroups of Rai, Magar, Tamang, and Sherpa. Each cohort, genetically distinct from the other yet shares the same Tibetan ancestry at varying degrees.

The use of race as a research variable is deeply rooted within the longstanding belief that race correlates to genetic similarities. But in actuality, the ways in which we differ have little to do with our ideas of race and more so with our genetic history. The misuse of race, ethnicity, and sex as population descriptors in genomic research creates a distortion of how it can be attributed to our health and a subsequent misapplication in clinical settings. It’s therefore crucial to understand the instances where data is misused and, when used appropriately, the context of its causality.